The Lady with the LampThe Story of Florence Nightingale, the Founder of Modern Nursing

12 May 2025

“The ‘kingdom of heaven is within,’ indeed, but we must also create one without”

—Florence Nightingale (1820–1910)

A refined English lady who became a caregiver for the poor in overcrowded hospitals. The first true researcher and founder of modern nursing. A woman who voluntarily devoted her entire life to the sick and wounded. Because of her, hospital sanitation and hygiene—especially in military hospitals—underwent a complete transformation.

She developed and implemented groundbreaking methods of patient care that are still used globally today. She changed the way the world thought about hospitals. The very idea of a “nurse” as we know it gained its meaning through her work.

Florence Nightingale served the suffering for a lifetime, believing that genuine faith must be expressed through love for others.

God’s Calling

“You are to do something very important—something only you can do.”

These words, spoken to 17-year-old Florence during a walk in the garden, stuck with her like a divine calling. From that moment, she couldn’t stop asking herself: What is it I’m meant to do?

Six years later, during a charity visit to a hospital, Florence was confronted with the brutal reality of poor patients’ lives. What she saw shocked her to the core: the unbearable stench, drunken caretakers unfit to help, overcrowded wards where contagious and non-contagious patients were crammed together. In that moment of anguish, she finally understood the answer she’d been seeking:

“Caring for the sick—that’s what I’m meant to do.”

The Cultural Climate

Nineteenth-century Victorian England was a textbook example of a patriarchal society. A woman’s life was decided for her before she was even born. A young lady of high society was expected to master etiquette, marry without delay, and have children. Work? Absolutely not. If a woman of noble background had to work, it meant either her husband had failed financially or died suddenly, leaving the family in debt. If she didn’t marry at all, society quickly labeled her an “old maid”—even if she was only 25.

A Calling Takes Root

“The hardest part is making the decision to act—after that, it’s all perseverance.”

—Florence Nightingale

Born into British aristocracy in 1820, Florence was the younger of two daughters. Her wealthy and well-educated parents were on an extended tour of Italy when their children were born: one in Naples, the other in Florence—hence the name Florence.

She received an exceptional education: literature, five foreign languages, mathematics, history, painting, and music. By all social standards of the time, her path was clear—find a suitable match and marry well. And she had opportunities.

One persistent suitor was Richard Monckton Milnes, a politician and poet. But after nine years of courtship, Florence turned down his proposal—even though she loved him—convinced that marriage would hinder her true calling.

Florence believed the life of a wealthy lady was dull and pointless. She felt a deep pull to care for the sick and wanted to address the root causes of their suffering. She often visited the sick on her family’s estate, bringing food, changing linens, and offering comfort.

Victorian-era hospitals in England were horrific: filthy, mismanaged, and dangerous. The sick were rarely treated properly, left unwashed, and often tended to by women with nowhere else to go—ex-prisoners, alcoholics, and women with rough pasts.

The upper class avoided hospitals entirely, believing them to be for beggars. They received care only at home. Hospitals were for the poor—those with no other option.

“I want to be a nurse,” Florence told her family.

Her parents and older sister were horrified. This was not behavior befitting a proper lady. Mr. and Mrs. Nightingale did everything they could to change her mind. But travel and fancy parties weren’t enough to distract her.

The Turning Point

“Illness is serious. Treating it lightly is inexcusable. You must love the work of caring for the sick—or choose another path.”

—Florence Nightingale

While traveling through Egypt and Europe, Florence studied patient care firsthand. She noticed how hygiene and proper nutrition significantly improved patients’ chances of recovery. She concluded that Catholic sisters in France and Protestant deaconesses in Germany were far more skilled in nursing than English caretakers.

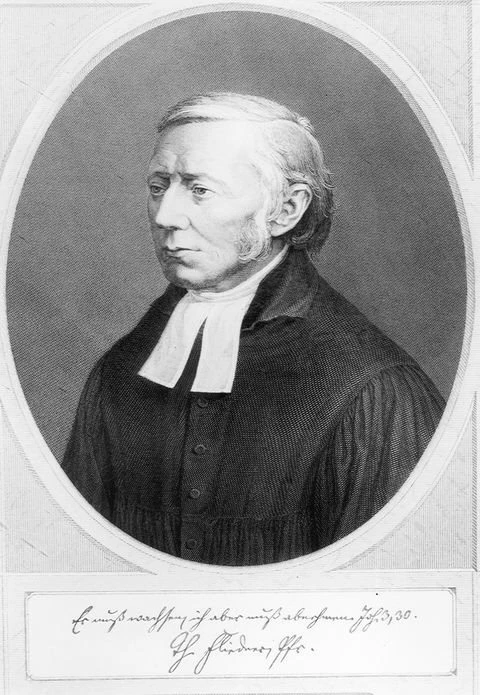

What impressed her most was a place called the Deaconess Institute in Kaiserswerth, near Düsseldorf, Germany—the first Evangelical school for training nurses. Eventually, it inspired the creation of nearly 80 similar institutes across the country.

It was founded by Lutheran pastor Theodor Fliedner. His own journey into caregiving began in 1833, when he cared for a lonely prisoner staying in his summer cottage. This experience led him to establish a hospital with 100 beds.

In 1851, Florence completed four months of nursing training at the Deaconess Institute. That practical experience would become the bedrock of her future work.

Two years later, at age 33, with her father’s permission, Florence took a position as superintendent at the Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen in London—a hospital serving governesses who worked in wealthy households.

Her father gave her a yearly income of £500 (around $65,000 today), allowing her to live comfortably while dedicating herself fully to her mission.

The Crimean War (1853–1856)

“All sick people turn toward the light, just like plants turn their leaves and flowers toward the sun. The room must be kept spotless. The floor should be wiped with a damp—not dry—cloth, polished with wax, and rugs must be beaten—those are real breeding grounds for filth.

The patient himself, of course, must be washed regularly: sometimes he shivers not from fever but from unchanged linens. Meals must be served strictly on schedule—even a ten-minute delay can throw off digestion for hours.”

—Florence Nightingale

In 1853, Britain and France entered a war against the Russian Empire on the side of the Ottoman Empire. Reports began to reach Britain about the horrific conditions in the military hospital at Scutari (now Üsküdar, a district of Istanbul).

Florence Nightingale, together with 38 volunteer nurses, arrived at the military hospital, where there was a severe shortage of medicine, hygiene was neglected, food was spoiled, and deadly infections were spreading rapidly.

Thousands of wounded soldiers with untreated injuries lay in their own blood and excrement on straw mattresses infested with bugs. At night, military doctors left them in pitch-dark corridors, with no one to care for them.

But Florence and her team weren’t allowed to treat the wounded. The military command only permitted them to serve food, sew, and stuff mattresses with straw.

Army officers were outraged that women would be tending to male soldiers. Hostile and crude, they insisted a military hospital was no place for women.

But Nightingale never backed down. With support from the Minister of War—who was a personal friend—and through sheer determination, she soon made real progress.

She secured large boilers for laundry, hired over 200 workers to renovate the hospital wards, and arranged for soldiers to send their wages home. She even wrote encouraging letters to the soldiers’ families herself.

Florence opened a reading room in the hospital. She also brought in renowned French chef Alexis Soyer from London to prepare nutritious, high-calorie meals for the wounded. The men were uplifted whenever the nurses read to them or simply sat and talked.

At night, Florence would light a lantern and walk the halls so the patients wouldn’t be afraid of the dark.

“She is truly a ‘ministering angel’ in these hospitals, and when her slender form glides silently along each corridor, every poor fellow’s face softens with gratitude at the sight of her. When all the medical staff have gone for the night, and silence and darkness fall over those rows of suffering men, she may be seen alone, with her little lamp in hand, making her solitary rounds.”

So wrote The Times, and from then on she became known as “The Lady with the Lamp.”

Her greatest victory came when a sanitary team from England arrived in Üsküdar and began cleaning the hospital—including the drainage systems.

The clearest evidence of her success was found in the numbers: in February 1855, the death rate was 42%. By June of that same year, it had dropped to just 2%.

While on the frontlines, Florence contracted Crimean fever. For nearly two weeks, she fought for her life. All of England—from Queen Victoria to common soldiers—prayed for her recovery.

The British public raised over £40,000 for their national heroine. The funds were later used to care for the wounded and to train future nurses.

Though she survived the illness, her health was deeply affected. She remained partially disabled for the rest of her life.

In 1856, when the war ended, Florence returned to England in secret to avoid the spotlight and settled into a quiet life at her family home.

The Legacy of Nightingale

“If you need a daily maid, you can hire one. But caring for the sick is a profession. A nurse should do nothing else but care for the patient.”

—Florence Nightingale

For the next 50 years, she devoted herself to reforming hospital administration and professional nursing.

In 1860, she founded a nursing school at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London. A humble, compassionate woman filled with the love of Christ, she transformed a disrespected role into a noble and skilled profession. Thousands of nursing schools around the world have followed the Nightingale model.

One of her most impactful achievements came in the 1860s, when she introduced trained nurses to workhouses across Britain. From then on, sick beggars were no longer cared for by other able-bodied beggars, but by qualified nurses.

In the 1870s, Florence mentored Linda Richards, known as “America’s first nurse.” After returning to the U.S., Richards went on to pioneer professional nursing both in the United States and in Japan.

“When Nightingale began, there was no such thing as professional nursing. The Dickens character Sarah Gamp, who preferred gin to her patients, was only a slight exaggeration.

Hospitals were places of last resort, with straw laid on the floor to soak up blood. Florence transformed nursing after her return from the Crimea. She had access to powerful people and used it to make things happen. She was persistent, confident, and outspoken—but she had to be, to accomplish what she did,” said Caroline Worthington, Director of the Florence Nightingale Museum.

For the last 14 years of her life, Miss Nightingale was bedridden and nearly blind. Yet she continued to work with the help of a secretary and welcomed visitors who sought her counsel.

At age 87, Florence Nightingale became the first woman to receive the Order of Merit from King Edward VII.

The Lady with the Lamp passed away peacefully in her sleep in London, August 1910.

The Florence Nightingale Medal

Every two years, 50 of the world’s top nurses are awarded the Florence Nightingale Medal “for true compassion and care for others.”

Established in 1912, it is the highest honor for nurses worldwide.

It is awarded to women who have shown extraordinary courage and dedication in times of war or peace—caring for the wounded, the sick, the disabled, or those whose health is at risk.

The medal may also be awarded posthumously, if the nominee died in the line of duty.

In 2011, Ludmila Vlasova, a nurse from Yenakiieve, Donetsk Region, received the medal for saving miners during the Karl Marx Mine accident on June 8, 2008.

Over the last hundred years, 24 Ukrainian nurses have received this prestigious honor.

The medal is awarded each year on Florence Nightingale’s birthday, May 12—the day the whole world celebrates International Nurses Day.

How to Uplift and Reform an Undervalued Profession | Florence Nightingale

A Heart Devoted to People… Florence Nightingale

Christians Who Changed the World

Florence Nightingale

Theodor Fliedner

Florence Nightingale

Prepared by the CITA Ministry press center.